Printing Industry Exchange (printindustry.com) is pleased to have Steven Waxman writing and managing the Printing Industry Blog. As a printing consultant, Steven teaches corporations how to save money buying printing, brokers printing services, and teaches prepress techniques. Steven has been in the printing industry for thirty-three years working as a writer, editor, print buyer, photographer, graphic designer, art director, and production manager.

|

Need a Printing Quote from multiple printers? click here.

Are you a Printing Company interested in joining our service? click here. |

The Printing Industry Exchange (PIE) staff are experienced individuals within the printing industry that are dedicated to helping and maintaining a high standard of ethics in this business. We are a privately owned company with principals in the business having a combined total of 103 years experience in the printing industry.

PIE's staff is here to help the print buyer find competitive pricing and the right printer to do their job, and also to help the printing companies increase their revenues by providing numerous leads they can quote on and potentially get new business.

This is a free service to the print buyer. All you do is find the appropriate bid request form, fill it out, and it is emailed out to the printing companies who do that type of printing work. The printers best qualified to do your job, will email you pricing and if you decide to print your job through one of these print vendors, you contact them directly.

We have kept the PIE system simple -- we get a monthly fee from the commercial printers who belong to our service. Once the bid request is submitted, all interactions are between the print buyers and the printers.

We are here to help, you can contact us by email at info@printindustry.com.

|

|

Archive for March, 2023

Sunday, March 26th, 2023

Photo purchased from … www.depositphotos.com

It’s easy to forget that commercial printing is more than just a process of putting ink or toner on paper, and miss out on all the other operations that contribute to the overall success of a custom printing job.

A lot of these processes follow the printing step and are therefore referred to as post-press operations or finishing operations. Strictly speaking, even folding and trimming the stack of press sheets after the ink has dried would fit into this category, but today we will focus on three post-printing techniques that give dimension to a printed product: die cutting, embossing/debossing, and foil stamping.

Above all else, commercial printing is a tactile medium. You become especially aware of this when you compare a 256-page perfect-bound print book with French flaps to the same book presented as a file on an e-reader. The print book has heft. The text and cover papers have a rough or smooth feel. And there’s usually a scent associated with a printed paper product.

The three post-press operations I have mentioned add to this tactile nature and accentuate the dimensionality of the printed piece (which is, above all else, a three-dimensional object).

Die Cutting

Die cutting is done on a letterpress. That is, it is a physical stamping process, unlike offset printing, which depends on a chemical property: the immiscibility of oil and water. (Oily ink and water do not mix.)

A letterpress performs a physical, relief-printing process (the image areas are raised above the non-image areas). In the case of die cutting, flexible metal rules are bent into the shape required (let’s say a square to be cut out of the front cover of a presentation folder). These rules are set into a wood base with the edge of the cutting rules raised above everything else. When the letterpress is operated with the presentation cover paper in place, the die rules will chop through the paper. Then the scrap (the portion to be removed) can be discarded by the press operator.

(A similar process can be done for scoring, which is the creasing of thick custom printing paper to allow for smooth, even folding. It can also be done for perforating, which uses a metal rule to punch a row of tiny holes in commercial printing paper so it can be torn smoothly by the end user. While these are also done on a letterpress, they can in some cases be done on an offset press, with the metal scoring or perforating rules attached to the impression cylinder of the offset press. Unfortunately, this eventually destroys the rubber blanket on that particular unit of the offset press.)

Die cutting is used extensively in product packaging. If, for example, you take apart a carton of tea bags from the grocery store (to the point at which all glued portions have been separated and laid flat), you will see that it is composed of an irregular form with a number of flaps. (The same is true if you take apart a presentation pocket folder.) The metal die cutting rules punch out this intricate shape, which when folded and glued yields a rectangular product box.

Dies are always an extra cost. In my experience they often cost between $250 and $500. That said, every time you reprint a job using the same die, you already have it on hand and don’t need to pay for a new die. You just have to pay for the die-cutting process. In addition, for standard dies that many customers might use, your printer may already have these on hand, so you may not need to pay for and wait for a new one.

Embossing/Debossing

Also using a metal die (in this case a two-part die), you can use a letterpress to raise or lower an image above or below the rest of the printing sheet (up to about 1/8”). You would do this after the custom printing component of the job. Otherwise, the pressure of the offset printing press would crush the sculpted image.

In embossing and debossing, one part of the two-part die pushes the design into the paper fibers, while the other part of the die receives this impression, allowing the paper to move forward or backward in accord with the image. This is done with heat as well as pressure to allow the paper to be sculpted more easily, and this adds a smooth surface to the embossed or debossed area as well.

Embossing and debossing dies (embossing raises the image above the rest of the paper, while debossing lowers the image) can be quite intricate, and the edges of various parts of the die can even be at different levels of depth. However, if the lines are too fine, they may cut through the paper (that is, the goal is to form the paper without cutting it).

In addition, if the dies are especially deep, they may need to be beveled (staggered in multiple layers) to avoid cutting into the paper, and this can make the image area of the embossing/debossing look smaller than it actually is.

So involve your printer early in the design process to ensure that your design will work on a physical as well as aesthetic level.

In some cases, you may choose registered embossing, in which the raising or lowering of the paper surface is in register with a previously inked image. This may also be the case if you’re foil stamping a job. For instance, you may want to register a foil seal and an embossing stamp for an award symbol on a certificate or book jacket cover, or even the words in the title of a print book on the book’s dust jacket.

If you just want to emboss or deboss a design on paper without registering it to previously printed ink or previously foil-stamped images, this is called blind embossing. In this case the three-dimensional raised or lowered effect is the complete design, without any printing.

Such soft “text papers” (i.e., high-end textured papers) as felt stock are good for embossing/debossing because they are thick, durable, and soft. This helps them take the impression of the metal dies better than a harder press sheet.

As with die cutting, embossing/debossing will require extra time (dies are subcontracted out by your printer) and will add to the cost of the custom printing process.

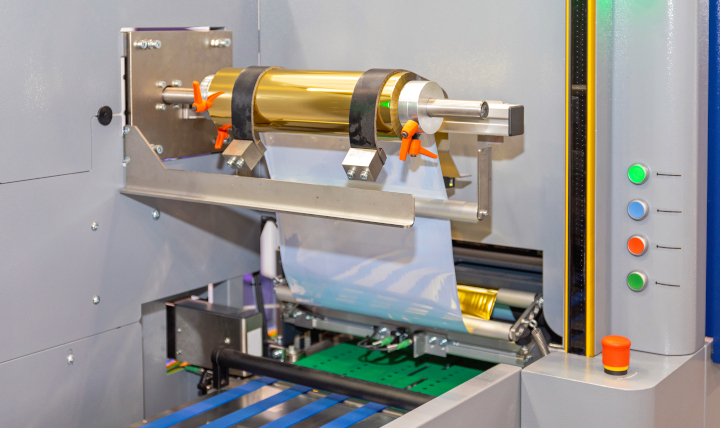

Foil Stamping

Another strike-on process used to embellish your print book dust jacket or even the cloth of the case binding itself is foil stamping. This is also good for the starburst seals on certificates of appreciation. In either case a metal die is created with the image area of the artwork slightly raised.

This die is then heated and pressed against a roll of thin foil, and the heat and pressure attach the foil to the substrate. The fabric of book covers actually accepts this process quite readily. In the case of certificates with raised foil seals, the foil-stamped certificates can then be embossed as described above.

Interestingly enough, this process can also be used for physical products such as pencils, pens, frames, and such.

In addition, you have a much wider range of choices of foil than you might think, including metallics, pastels, patterns, and even clear foils and foils that match the background (such as gloss or dull black to be attached to black paper). So in this way you can create contrast between the text and background.

Foil stamping is great for rendering text on dark paper, for instance an invitation with white lettering on a black background. Since offset inks are transparent, it would take two or three passes with ink to create a completely opaque image, whereas the foil is already opaque, so all you need is one pass through the press.

The best paper to foil stamp is either a textured stock (a premium “text” sheet) or even a high quality bond paper.

Granted, as with die cutting and embossing/debossing, foil stamping requires the cost and time involved in cutting (chemically or by hand) a metal die.

Getting It Printed, a text on commercial printing technology by Mark Beach and Eric Kenly, notes that foil can blister if applied over inks containing silicone or wax, or even over coated paper. In addition, applying foil over too large an area (more than eight square inches) may also cause blistering.

On the plus side, Getting It Printed mentions that these plastic foils can stretch, which makes for a successful pairing of embossing and foil stamping.

Posted in Post-Press Finishing | Comments Off on Custom Printing: Three Sculpted Finishing Operations

Sunday, March 19th, 2023

Photo purchased from … www.depositphotos.com

A long-term, mutually beneficial business relationship with a printer sometimes ends. Perhaps the printer goes out of business or starts to not be as responsive as in prior years. Maybe their prices even rise dramatically, making the company no longer an option. What can you do?

In this light I have a case study to share. One of my commercial printing clients produces a color swatch book on a regular basis. These tiny, screw-and-post books are like PMS swatch books for those looking for make-up and clothing colors that will complement their complexion and hair color.

Along with this set of color swatch books, my client prints larger chin cards with a die cut for the person’s neck. These 8.5” x 11” chin cards allow the user to hold a large color swatch under her chin to see how a particular hue will look with her skin tone and hair color.

The cards are 8.5” x 11”, 14 pt. in thickness, with a semi-circle die cut for the chin, and with lamination on both sides. One side of each card is a big swatch of color bleeding on all four sides. The other side is text in black ink only. The total set comprises 72 pages (35 colors with information on the back of each, plus one single-page (front and back) set of instructions.

Losing a Printer

My color-swatch-book and chin-card client recently lost her printer based on issues with management. This particular printer had produced 50 sets of her chin cards every other year or so. The colors had been faithful to her expectations, and there had been no banding or artifacts in the solid, digitally printed colors, so it had become an easy reprint on a periodic basis. A boon to the printer (it was regular, straightforward work) and to my client (the end result was predictable).

So losing the commercial printing vendor was unfortunate. I had actually gone through a similar loss of a printer for my client’s color swatch books for a different reason several years prior. This vendor had upgraded the software on their HP Indigo digital laser press, and for whatever reason a number of the colors of the (smaller than 2” x 3”) swatch books were no longer accurate. This was a harder problem to solve, and it also came down to finding a new printer.

Digital vs. Offset

One of the challenges with replacing the custom printing supplier for the color swatch books (and this will also be true for the color chin cards) was to ensure color accuracy and smooth, even color laydown (compared to offset printed solids). All colors are percentage builds made from the four process colors. There are no PMS colors (since there may be a total of over 100 distinct hues that show up in some of, or in each of, the 28 master copies of the color swatch books).

This would be prohibitively expensive to produce via offset lithography, since it would require multiple passes on an offset press for what would in many cases be only a few copies at a time of the individual swatch books (so many copies of each of the 28 master versions).

For the color chin cards, the same would be true since my client only prints about 50 copies of the 72-page set at a time.

In both cases the limited press run for the individual sets, plus the use of so many colors, requires an accurate and consistent digital press. In my mind that includes the HP Indigo plus perhaps a Konica Minolta plus a Kodak NexPress, although I’m sure in the last several years other vendors have stepped in with equally accurate color digital printers.

With the loss of the color swatch book vendor, and in the most recent case the loss of the color chin card vendor, selecting a replacement has been and will be dependent on a physical proof of all pages.

So I have requested pricing for (in the case of the chin cards, since it’s the current job needing custom printing vendor replacement) a full hard-copy proof from the digital press in question, whether it is a digital laser press or a digital inkjet press (depending on the new vendor).

The color proof will ensure that the color builds (percentages of cyan, magenta, yellow, and black) that my client had specified in her art file (she had kept a digital copy of her chin cards from the prior print run) match her expectations.

This is not always the case for all colors for all commercial printing vendors using a variety of digital presses. And soft proofs (PDFs on screen) of the color swatches (2” x 3” color swatches or 8.5” x 11” color chin cards) would not necessarily present the colors as they will eventually look when actually printed. After all, in the case of a computer monitor proof, the colors are created with red, green, and blue phosphors, whereas on a proof made on the actual press, the colors will have been created from the actual cyan, magenta, yellow, and black toners or inkjet inks.

In my client’s case the die cut and the lamination will be irrelevant, and not including these elements on the printer’s proof will keep the price down ($75.00, approximately, from two of the vendors I’ve approached). I think the cost of such a proof (rolled into the total manufacturing cost by some printers) is an investment, not an expense.

Banding and Artifacts

In my experience, some digital presses also produce solids (in this case up to 8.5” x 11” for the chin cards) that may not be as even a laydown of pigment as with oil-based, thick, offset-printed ink.

Sometimes there are artifacts (stray marks or lines) or banding (usually but not always in gradations from a light tint to a darker shade of a color). I’m not sure whether the banding is a reflection on the number of steps in the gradation (not an issue in the case of my client’s chin cards) or the PostScript (page description language) code of my client’s art file, or even in the nature of the process (spraying ink through nozzles—which sometimes clog) for the inkjet option or using toner particles suspended in fuser oil for the digital laser option.

Regardless, heavy ink coverage can cause problems. And nothing will be as effective in allaying my client’s concerns (and mine) as a hard-copy proof. It will ensure color fidelity (some colors seem to be more problematic than others) and the absence of banding. And once the new printer has proved it can provide an acceptable printed product, my client will have a home for this repeat job for many years going forward.

The Die Issue

Unfortunately, my client will need to have the die for the semi-circular cut out (for the user’s chin) remade. Granted, she paid for it once (approximately $275.00) and it was then used for successive runs of her job. And strictly speaking it is hers (according to commercial printing trade customs). But you could argue that it is only a component of the overall manufacturing process and therefore it belongs to the original printer. Struggling over this for $275.00 may not be worth it.

Availability of Materials

One of the things I’m finding is that not every printer can get the same lamination film for some reason. The job was originally produced on 14 pt. cover stock with 3 mil laminate on both sides of the chin cards. In the cases in which printers have only been able to get 1.2 mil laminate, I have asked for thicker cover stock for the chin card boards.

There is usually a work-around. This is mine.

Other printers may have different approaches. In my case, I think my client will be happy with the printed product as long as the total thickness of the base stock and the laminate on both sides of the cards feels about the same as samples from the prior press runs.

The Takeaway

So there are ways to get around losing a commercial printing supplier, even for a printed product that is a repeat job with colors that may not be easy to match (several of the printers “no-bid” this job outright, concerned that my client would not accept potential color banding or less than perfect colors).

If you have a job like this, it’s worth collecting bids from a number of prospective vendors. The PIE website (I have found) is always a good way to get new printers. Referrals from other clients or other printers that can’t for whatever reason do the job for you would be another option.

But in all cases I feel very strongly that checking an actual, physical proof will put your mind at ease, proving whether the vendor can or cannot provide your required level of quality. Granted, in some cases like these (multiple color builds produced on a digital press), you may need to have some flexibility. Not everything will be 100 percent perfect. Fortunately, my client understands this as long as the hues are reasonably close to the intended color.

But again, all of this will be visible in a good hard-copy proof, and this can help you develop a new long-standing, mutually supportive business relationship with a new printer. It’s a little bit like a marriage. It takes work, but the benefits make it worth it.

Posted in PrintBuying | Comments Off on A Case Study on Replacing a Commercial Printing Supplier

Sunday, March 12th, 2023

Photo purchased from … www.depositphotos.com

I’m a great believer in marriage. Weddings give you an opportunity to use one of the most artistic printing techniques (as well as one of the oldest) in existence: engraving. In fact, since my fiancee and I teach art to autistic students, I could very well share this same information with our students, because there is a long history of engraving in the fine arts as well as the graphic arts.

Engraving is an art form that lends itself to special occasions, such as weddings. However, it is also quite appropriate for corporate materials such as invitations to special gala events, letterhead, and business cards.

The Engraving Technique

Engraving is the opposite of letterpress. In letterpress, raised image areas and text print content onto commercial printing paper. In engraving, lines of images and text are incised into either steel or copper printing plates. Thick ink is wiped onto the plate and then wiped off, leaving ink only in the incised image areas.

Keep in mind that the dimensions of the engraving work tend to be very small (such as the size of a business card or invitation). When the intense pressure of the engraving press is applied, it forces the custom printing paper into the incised type and image areas of the inked plate, and the paper absorbs the ink. At the same time, the image areas are raised slightly by the intense pressure. So when the final piece comes off the press, the back of the sheet is slightly indented behind the typescript letters, and on the front of the sheet these very same printed elements are raised.

To compare this to the most common current form of commercial printing other than digital printing (i.e., offset lithography), offset printing plates are flat (neither raised like letterpress nor lowered, or incised, like engraving). In offset printing, what keeps the ink confined to the image areas is a chemical property of oil and water (or oily ink and water). That is, oil and water do not mix, so it is possible to separate them on a flat commercial printing plate.

To compare all three custom printing techniques in this light, engraving is an “intaglio” (recessed-image) printing process, offset lithography is a “planographic” (flat-image) printing process, and letterpress is a “relief” (raised-image) printing process.

Beyond the aesthetics of a special business card or invitation, engraving provides the sharpest printed impressions of any custom printing technique. Therefore, it is used to print currency and stock certificates as well.

Engraving plates are either steel or copper. According to my go-to book on printing, Mark Beach and Eric Kenly’s Getting It Printed, steel plates will allow for much longer press runs than copper plates. (Copper plates are usually good for press runs up to 5,000 copies, and then they deteriorate.) However, engravers usually only offer a few typefaces on steel plates.

Engraving plates can be imaged in the following ways:

- The lines can be incised by hand using tools. (This is used for steel plates.)

- The type and imagery (very simple line drawings, for instance) can be chemically burned into the metal if you’re starting with a “mechanical” (hard copy, actual type and imagery pasted up on paper), which is pretty much an extinct option now. (This is used for copper plates.)

- The type and imagery can be burned into the commercial printing plate with a laser from digital art files (more common). (This is used for copper plates.)

When you’re designing for engraving, keep in mind that the inks are thick and opaque, which can make them a great choice for a darker paper stock. (They are more striking than transparent offset inks printed on darker commercial printing paper.) Also they come in gloss and dull formulations, which will give you options. For instance, the gloss inks may even appear a bit metallic.

One of the most important things to remember if you are buying engraving services is to choose an appropriate, high-quality paper that will showcase the aesthetics of engraving. Let your printer help you choose the paper stock.

Another thing to remember is to ask the printer to confirm the heat tolerance of your final printed product if you intend to print names and addresses on a laser printer. In some cases the high heat of a laser printer could damage the engraved product.

Engraving requires intense pressure, as noted earlier, so it lends itself to small presses printing small images. Getting It Printed notes that anything larger than a 4” x 8” area would require an additional pass through the press. (For instance, your printer may do one pass for the top of your letterhead and another pass for the bottom of your letterhead.)

An Option to Engraving

But what if you can’t afford the expense of engraving? Or maybe you want something for larger-format printed pieces. What are your options?

Thermography is a hybrid printing technique that actually starts with offset lithography. You may in fact have seen thermographically printed business cards and thought they were engraved, because the type and imagery are raised as in engraving. (One key give-away, however, is that the underside of the printing paper is not indented behind the type letterforms.)

Thermography starts with slow-drying offset printing inks that are dusted with thermographic resin powder after the offset printing step. This powder sticks to the offset ink and “takes on the color of the underlying ink, but may not match perfectly” (Getting It Printed, p. 138). Excess thermography powder (powder not covering type or other image areas) is then vacuumed away, and the printed piece is heated. Heat melts the thermography powder into the offset ink, but it also causes the powder to bubble up (hence the raised effect that simulates engraving).

In my experience, two things are important to remember with thermography. The first is to keep things simple. You can create an attractive, raised effect, but if you try to reproduce anything but the coarsest halftone screens, the screens may plug up and look uneven. (I personally did this once about thirty years ago, so I encourage you to learn from my mistake.)

Also, there is a chance of your receiving a printed piece in which the ink looks stippled (a pattern of tiny indentations, like the skin of an orange peel). So ask your printer for samples, and make sure he is skilled in thermography and can avoid this stippled effect. You want the powder to rise as it is heated, and you want a uniformly glossy appearance, so your printer must be able to control the offset ink application, heat, and thermography powder application.

That said, you don’t have to use thermography only for business cards or letterhead. Getting It Printed suggests applying thermographic printing to perfect-bound print book covers, for instance, perhaps highlighting the title of the book by making it colorful, raised, and textured.

If you choose thermography for a printed item, you have a choice of fine, medium, or coarse thermography powders, so you can use fine resign powder for fine lines and thicker granules for larger areas of type or color solids. However, too large an area of color thermography might result in a blistered appearance. Also, printing across a fold will result in cracking of the dried thermographic powder.

And finally, thermography does not have the highest rub resistance and can therefore be scratched. Also, thermographically printed ink does not tolerate the heat of a laser printer and can lose its “rise and luster” (Getting It Printed, p. 139) if heated.

Posted in Printing | Comments Off on Custom Printing: Choosing Engraving or Thermography

Sunday, March 5th, 2023

Photo purchased from … www.depositphotos.com

About a year ago I got a phone call from a large commercial printing consolidator (a company that buys and then operates print shops across the nation and sometimes in other countries as well). My contact said the consolidator couldn’t get paper for one of its clients. This would be a huge, recurring job involving custom printing, perforating, and die cutting labels.

It was a sweet job, and I had good contacts, one who could print the job in China and another in the US in the Midwest. But when all was said and done, I didn’t get the job and I’m grateful for that. Between the client’s demands for specific paper and that paper’s unavailability even among my contacts, I learned a lot about the current paper shortages, supply chain issues, lines of ships waiting to dock at US ports, and economics in general. I couldn’t have received a better education back in college.

That said, now it’s a year later. For those of you who produce recurring print jobs (as designers, print buyers, art directors), what is the current status of commercial printing paper?

The Current State of Paper Sourcing

With this question in mind, I went online and found several good articles, which I draw from (and quote) in the following blog posting. If you want to do your own research, you might check out “2023: Will the Paper Chase Persist?” by Toni McQuilken, www.piworld.com, 02/15/2023, and “US Printing Paper Demand Slows Down in a ‘More Normal’ December as Panic Buying Ends,” by Renata Mercante, Fastmarkets, 12/21/2022. Both articles, and others, can be found online.

That said, here is the gist of what I have found.

In the past several years we have had shutdowns due to Covid, labor shortages, weather issues, higher costs for shipping, and general disturbances in the supply chain (both for US-based and imported paper). Also, many paper manufacturers in the US changed from producing commercial printing paper to producing packaging board. This reduced printing paper availability (some grades and weights more than others).

When combined with a healthy (and in some cases increased) demand for commercial printing paper (by customers and therefore custom printing suppliers), the reduced paper supply drove up prices (for the paper component of printing).

This year, 2023, according to John Crumbaugh, product manager of ColorPRO Technology, Media Operations, at HP: “The supply chain for producing printing paper is still tight, but there are signs that it’s beginning to loosen up and should be much improved in 2023.” “In North America, the paper mills are operating at or near capacity, but the analog market appears to be slowing, and imports are beginning to increase, so paper is more available than earlier [last] year” (John Crumbach, as quoted in “2023: Will the Paper Chase Persist”).

One reason the market is beginning to slow, according to this article and others, is that printers have slowed down their panic buying and are now using the inventory they had amassed. Since paper availability has increased and the end users (apparently) are a bit less demanding, printers have recently been able to both use what they have in inventory and also selectively buy paper to add to their in-house supply.

That said, paper imports have arrived a bit faster (with easier access to US ports). However, this is somewhat mitigated by the lower number of domestic mills producing paper (as noted before, a lot of them had been converted to paperboard making). So paper is more available, but its price isn’t coming down anytime soon.

Plus, the concept of “just-in-time delivery,” at least in paper sourcing, is not viable now and will not be for the foreseeable future.

According to Crumbaugh, as quoted in “2023: Will the Paper Chase Persist,” “Pricing for printing grades of paper have increased up to 40% over the past five years.” “Supply chain issues, transportation, and increased cost of production have driven pricing up very quickly. Pricing is likely to stabilize as opposed to dropping quickly, as many of the increased cost factors are still in effect.”

In short, paper is available, but the cost of the paper for a commercial printing job (and this can be a large portion of the total cost of the job—especially for print books) will keep overall custom printing prices high.

According to “2023: Will the Paper Chase Persist,” these are the paper grades affected (Toni McQuilken includes comments by a number of printers in this light as well). According to Crumbach (as noted earlier), these papers include “uncoated text and cover,” “some packaging grades, especially premium grades,” and wood-free paper grades. Plus, “Coated, as well, is difficult for both popular mid-range weights, as well as heavyweight point stocks” (John Crumbach, as quoted in “2023: Will the Paper Chase Persist”).

Importing paper has made things easier, but this has not completely mitigated the effect of many domestic paper suppliers’ having gone offline in the past several years.

At the same time, according to “2023: Will the Paper Chase Persist,” some papers that weren’t available a year ago are now more accessible, such as 70#, 80#, and 100# coated book papers (“mid-range weights, in general”) (“2023: Will the Paper Chase Persist”), and these are accessible in various sheet sizes for different-sized printing presses.

What to Do (for Printers)?

“2023: Will the Paper Chase Persist” suggests the following approach to the current state of paper sourcing, at least through this year:

- Think ahead. “2023: Will the Paper Chase Persist” encourages printers to plan for the workflow rather than stockpiling paper. This means keeping good relations (and open communication) with paper suppliers. McQuilken’s article especially notes that mills do not treat spot-buyers of paper as well as those who have developed mutually beneficial, repeat working relationships with the mills. McQuilken suggests that printers evaluate their projected paper needs for upcoming jobs on a monthly basis (rather than a quarterly basis).

- Don’t buy in a panic, but also don’t assume “just in time” sourcing will work.

- Be flexible. It is smart at this point to be open to alternative papers suggested by mills.

- If you are a printer, McQuilken suggests diversifying. That means perhaps even buying new equipment to be able to handle different commercial printing jobs in different ways on different presses, should paper for one press be more difficult to source. This will at least keep printers, and pressmen, from being idle in difficult times.

The Takeaway for Designers

Many of you who read these PIE Blog articles are not commercial printing suppliers, but rather individual print buyers in for-profit and non-profit organizations. Most of McQuilken’s suggestions will pertain to you as well.

In short, you will benefit from planning jobs earlier than in prior years. You can’t bring printers into the equation too early. Talk to your suppliers. Keep them in the loop.

And depend on their expertise. When they suggest alternative stocks that might work as well as your preferred custom printing paper, keep an open mind.

Posted in Paper and finishing | 2 Comments »

|

|